In a previous post I looked at who might be using materials deposited in endangered languages digital archives. In this post I will look at searching for information in several of the larger archives.

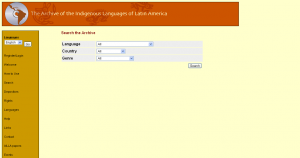

The Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America (AILLA) has a simple search interface which allows users to find materials by Language, by Country or by Genre using drop down menus that contain a list of search terms (click on the image to enlarge).

I tried searching for “Educational Material” and got a list of 56 deposits presented in no apparent order (click on the image to open it and again to enlarge).

Details about particular deposits can be found by clicking on Details link on the right-hand side. If relevant files are publicly available then they can be downloaded or played from this detailed page of information about the individual item.

The Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (Paradisec) has a form-based search interface that requires the user to understand the metadata categories used by the archive. While it is possible to search by language name, dialect, or even village, or to find deposits according to who collected them, it seems that nothing about the content of the deposited materials is searchable. So I could not work out a way to find “Educational Material” in Paradisec for example.

To access the actual files in Paradisec one must be a registered user and login to the system before being able to download materials.

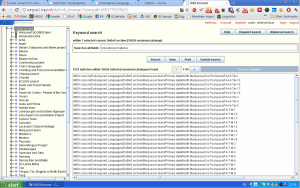

Users of the archive of the Dokumentation Bedrohter Sprachen (DOBES project are invited to “Come in and have a look” on its home page. There are 15,626 sessions available in the archive but searching for materials in DOBES requires using the “Metadata browsing” IMDI browser tool which is a Java applet that runs in the user’s web browser (so you must have Java installed and enable cookies). This presents the user with a hierarchy tree that is navigated by clicking on nodes in a graphical representation on the left of the web page. If the user right clicks on a node (I don’t know how Macintosh users do this and no instructions are given on the site) several options are presented, including keyword search. I selected “Metadata search” which opens up a simple keyword search interface and tried searching for “Educational Material” — this returned a list of 1223 session names.

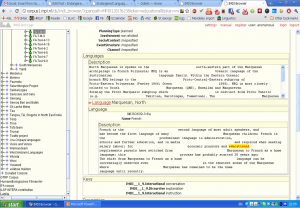

Clicking on one of the session names in the list brings up individual file information, indicated by a green bag (but be prepared to wait as the Java applet has to reload, open a new window, move down to the relevant node in the hierarchy tree and display the stored metadata). When I tried this with a random line in the list I ended up at a Marquesan deposit for a “Farm Animals game” in which the word “educational” appears in the description of the rôle of French in the Pacific!

To access the actual files one must be a registered DOBES user and login to the system. Note that DOBES has an additional sophisticated search function which enables users to search for annotations within Toolbox and ELAN files in the archive (probably only linguists would be interested in this). Thus it is possible, for example, to search across a set of DOBES deposits for a given morphemic gloss such as “ERG”.

Note that I also tried a search on “Teaching Materials” and this returned files with “teaching” anywhere in the metadata description, such as one from the Chintang and Puma project where we are told that Nepali is used in teaching in Nepal.

The Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS (ELAR) has a new home page and a new search capability designed and implemented by Tom Castle, Ed Garrett and David Nathan. This enables users to search the 7,587 resources in the archive in several ways.

The search interface is built from the metadata provided by depositors and classified into several types: Country, Language, Type, Tags, Genre, Topic, and Participants. There are boxes on the lefthand side listing all the terms used by depositors to describe their materials. Thus, the “Genre” list has the following (the numbers after each term reflect the number of file bundles with that categorisation):

Bislama version (32)

Chronicle (13)

Commentary (2)

Community materials (17)

Consonant contrasts (48)

Conversation (138)

Culture (13)

Custom description (13)

Custom narrative (16)

Custom story (1)

Description (53)

Descriptive narrative (3)

Descriptive (3)

Dictionary Materials (131)

Directional story (4)

Discourse (8)

Doctoral dissertation (1)

Elicitation (802)

Encouraging speech (2)

Ethnographic (13)

Failed Recording (7)

Folk Definition (15)

Folk Tales (20)

Folk tale (23)

Frog story (11)

Grammar Materials (63)

Grammar Qs (14)

Grammar elicitation (8)

Historical description (21)

History (26)

Humor (7)

Interaction (4)

Interview (14)

Kastom story (30)

Kastom (6)

Kinship terms (3)

Language teaching (17)

Letter (4)

Lexical items (24)

Lexicon (6)

Local history / personal story (2)

Local history (4)

Love song (70)

Metadata (6)

Miscellaneous (9)

Music (14)

Myth narrative (16)

Narration (12)

Narrative from visual prompt (4)

Narrative (114)

Non-traditional narrative (1)

Nuestras tradiciones (4)

Nuestras vidas (4)

Nuestros cuentos (7)

Oratory (3)

Personal history (3)

Personal narrative (3)

Personal story (51)

Personal (2)

Picture/video description (11)

Planned (translated) myth narrative (5)

Planned interview (2)

Prayer (2)

Praying (2)

Primary Data (34)

Primary Text (1158)

Procedural text (10)

Procedure (19)

Ritual dance (5)

Ritual singing (3)

Route description (10)

School Materials (11)

Secret/Sacred (4)

Semi-spontaneous interview (2)

Sentence trans (52)

Song (108)

Songs (21)

Speech (2)

Staged event (50)

Stories (19)

Story (11)

Survey (5)

Swahili summary (2)

Talk (16)

Teaching materials (17)

Text (57)

Text-based elicitation (21)

Texts (62)

Tonal contrasts (35)

Traditional games (2)

Transcription (11)

Transcription/translation (29)

Transcriptions (not yet categorised) (2)

Translation (19)

Travel (1)

Video recording of everyday activity (4)

Vowel contrasts (34)

Word list (18)

Word/phrase trans (57)

Wordlist (4)

Notice that ELAR does not insist in standardisation of metadata categories (or require them to be in English) but allows depositors to express information about their materials which they consider to be relevant and important.1 This results in some minor variation in classification (Narration versus Narrative, for example) or potentially synonymous categorisation (eg. Personal history versus Personal narrative, perhaps). One nice feature is that users can directly search for particular individuals who contributed to deposits as speakers.

I tried searching for “Teaching materials” in the Genre category (“Educational material” was not in the list) and this gave a listing of 17 bundles of data:

ELAR tags all of its materials for access and usage status using its URCS system (U = open to all, R = researchers, C = community members, S = subscribers approved by the depositor or their delegate) so any bundles that are tagged as U will contain files that can be downloaded or played immediately by any registered user (there are 4,217 such bundles in the archive’s collection, ie. over half of the total deposited material is immediately accessible).

There is now a wealth of resources available on endangered languages in these archives and others, and I encourage readers to access them and explore the wonderful videos, sound files, pictures and text materials that await them.

Notes

- Metadata is generally understood to be data about the data, recorded to ensure that its context, meaning and use can be properly determined. As I noted in a previous post “early work in language documentation starting around ten years ago was heavily influenced by library concepts (eg. Dublin Core), and … key metadata notions were interoperability, standardisation, discovery, and access … Today, however, we see more focus on expressivity and individuality in metadata descriptions that researchers are creating, and increasing emphasis on protocols, meta-documentation (documentation of the documentation itself), greater clarity on stakeholder rights and responsibilities, and more diverse ways in which researchers are creating and manipulating their metadata.”

Follow

Follow

dear Peter,

Thanks for that useful review.

Another catalog which is useful is the “OLAC Language Resource Catalog” (http://search.language-archives.org/), which harvests several repositories including Paradisec, AILLA, SIL, CRDO… It uses an interface (ergonomically similar to the new ELAR), which makes it possible to quickly filter and sort results. For instance I just did a search on “all narratives that are accessible online, ranked by language”, and got these results: http://search.language-archives.org/browse.html?browse=subject_language_facet&fq=online_facet%3A%22Yes%22%20AND%20discourse_type_facet%3A%22Narrative%22&browse.sort=true. Pretty intuitive (even though the interface is less sophisticated than ELAR).

Also, there are some interfaces that one can develop on one’s local computer, and which are not (yet) available online. For example, I recently discovered how players like iTunes could be used to efficiently organise, search and display a whole collection of fieldwork archives. You can filter by genre or participant, search the title or the village, and so forth. If you’re interested, there’s a little demo on this page: http://alex.francois.free.fr/AF-audio-itunes-e.htm.

cheers,

Alex

Surely you can’t do a review of language archive searches without mentioning the two search engines that combine many of these language archives (and many more) into a one-stop shop?:

• The OLAC search engine at http://www.language-archives.org, and

• The OLAC search engine at Linguist List

While these engines are not tailored to the specific metadata categories of each of the indexed archives, it does provide a much broader coverage.

If my search was for a specific language, that is definitely one place where I would start – or I could start at google because the OLAC records that are the core of these two search engines are indexed by google as well. That way I might find records in more than one archive.

Tom and Alex

Thanks for your comments and pointing to OLAC. My piece is specifically about searching for endangered languages materials, not anything that is in a language archive. I tried playing with OLAC before I wrote this post and found many problems with it — perhaps I should have included mention of these in my post.

1. OLAC searches across any language archive that provides metadata to it, and there seems to be no way to limit search to only endangered languages

2. the list of participating archives does not include DOBES or ELAR, so you won’t find materials stored in them if you search using OLAC

3. the search interface is indeed easy to use, and allows filtering by various criteria, eg. whether the resource is to be found online, by language family, country, linguistic field, etc. So I found the search facility to be very usable

4. I did an OLAC search for “educational material” and this returned 1,541 items, of which 1,412 are in Spanish and 1,380 are in Yuracare (an Amazonian language spoken in Bolivia). I then filtered the search to “online” only — this returned 22 resources, of which 10 are in Tok Pisin and stored in Paradisec. So at least using OLAC I could find resources in Paradisec, however they are not in an endangered language.

5. strangely enough, none of the 56 resources I found in AILLA using this same keyword term in AILLA’s search facility (described above) were found by OLAC. I ran the OLAC search again for “educational material” looking only at AILLA and got the result: “No results matched your search”. So it seems that OLAC can’t find resources that are clearly categorised and findable at the member archive itself.

Tom mentioned Google in his comment — this might be useful “[i]f my search was for a specific language” but if one is looking across languages it doesn’t help much. Searching for “endangered language educational material” returns 31.8 million hits in Google without the quotes and zero hits with them! Trying “endangered +language +educational +material” where all the search terms must be present returns 3.19 million hits, the first of which is this blog post! Although Google Advanced Search can be filtered by language this only applies to the 46 languages Google recognises, and you cannot filter by a type of language, such as endangered languages only. Maybe there are ways to search on Google for things like “narratives in endangered languages” but I couldn’t figure out how to do it and get anything usable as a result.

Hi Peter,

To respond point by point,

(1) Yes, it is indeed the case that records in OLAC do not have (un)endangered or “degree of endangerment” as a metadata field or search field. In fact the only way I can see at the moment is to find a list of languages labelled as endangered, or to go directly to a specific archive specialising in endangered languages. But of course making a binary distinction of (un)endangered for a given language is sometimes a tricky business as I’m sure you’d agree! What OLAC does provide however, are filters like “Language Documentation” as a Linguistic Field. This seems to narrow things down a bit. Here is a search for education* OR teach* AND Linguistic Field: Language Documentation. Sadly, Tok Pisin and Arabic, amongst others make it into the results. As with all search engines, I’d probably try a few other things too. Of course, filtering it to archives that specialise in endangered languages would also be a good way to start.

(2) Yes, I’d have to agree with you that it is a shame that ELAR and DOBES are not currently exposing their collections via OLAC. I seem to recall for DOBES that they had made the initial steps, but there were some specific technical reasons that providing harvestable records didn’t quite work. Do you know if there are any plans for ELAR to provide harvestable metadata for OLAC? I think it’d be really great if the ELAR collection was accessible through this search mechanism.

(3) Yes, I’d also agree with you here. I have to admit, I am only now playing with this new interface for the first time, and I think its great. Its a fantastic improvement over the old search mechanism.

(4) Yes, I’d have to concede that searching for educational materials on OLAC is not so straight forward, but I think the advanced search goes a long way towards finding quite specific results, and again, it has the advantage of searching over a number of archives/languages.

(5) Yes, it seems that multiple advanced searches are the way to go. But then that is always the way when searching across large sets of semi-structured data. I think it is important to mention that OLAC is an aggregator of data provided by the individual archives. The degree to which each archive does (or is able to) provide good quality OLAC records depends on their individual implementations of a translator between their own records (and the metadata fields they record) and the OLAC record format. If you had trouble finding those records in AILLA via OLAC, I think it would be worthwhile letting them know – perhaps they can improve their translator such that those records would be exposed.

(6) / Google: I think I was only suggesting that because the data was exposed to google (and this is not always the case with databases/catalogues for instance), it could be found through that avenue. I wouldn’t for instance suggest google as a way to search for the PNG language “One”! But I should also say that most searches that I do on google have a million or more hits… what really matters is where the results are on the list. Searching for “Momu Language” for instance, may return 43,000 results for me, but the first page is full of useful links (some of them are even OLAC records!). Searching for ‘”endangered languages” “teaching materials” OR “educational materials”‘ got me a whole bunch of interesting links.

Btw Alex: Wow! That iTunes collection is pretty impressive. …how long did that take?!?!

And also a correction to my comments above, is does seem that DOBES is available through OLAC via the IMDI to OAI bridge (how’s that for number of acronyms in a single sentence!). But also, that the AILLA listing is perhaps not current, and so OLAC seem to be not the best way to finds materials in that archive.

Haha… now Tom can you please do a tree diagram of the above sentence, with all acronyms extrapolated of course. 🙂

ugh, dreadful on both counts…acronyms and grammar/punctuation.

Lets try that again:

And also, a correction to my comments above: it does seem that searching DOBES is available through OLAC via the IMDI to OAI bridge. But also it seems that the AILLA listing is not current, and so OLAC isn’t the best way to find materials in that archive.

There you go Wamut, parseable sentences, and now with extra links 😛

Peter and Tom,

Thank you for links to all these databases – I am currently compiling materials for numerous endangered Australian languages with very little written about them – so this has been most helpful.

Alex, you are ever impressive. Great work on your iTunes field archival interface. It looks fantastic, and how smart of you to use a program that is so accessible. I will definitely be passing that on.

Kate