Of the 7,000 languages in the world today, most have little presence on the internet.

What records there are in these languages are often religious translations from large languages and so, while being a valuable set of texts in the language, they have little local cultural content. For some of these languages, there are recordings made by outside researchers in the past, of local traditions, histories, and personal life stories. These recordings were then stored in various locations and may never have been played again. If they can be found and digitised, they can be made available to the people recorded or their communities. This is the work that PARADISEC has been doing since 2003.

When we do receive these collections, they rarely have more than a few notes written on to the tape box describing their contents. If we could transcribe what is being said it would give us a searchable index of the recordings. We are all familiar with speech-to-text (ASR) systems that can caption our meetings and our youtube videos. These system work well for mainstream languages, and the big tech companies like google are keen to tell us they can recognise 80 languages for ASR (here). They say here they can translate the text of 249 languages.

There are now a number of research projects aiming to build ASR for small languages, using very small training sets, and getting promising results.

Over the past three years our team has worked with an Australian government agency on the Pacific Creoles project, to record 90 hours of spoken Bislama (Vanuatu), Solomon Islands Pijin, and Tok Pisin (PNG), and to transcribe 60 of those hours. The aim of this is to create tools for Australians who work on humanitarian missions after disasters in these countries, like earthquakes, cyclones or tsunamis, and so they are the topics discussed. The recording and transcription were done by our researchers (see below) and by local teams in those countries, and the resulting materials will be openly available in PARADISEC once they are finished.

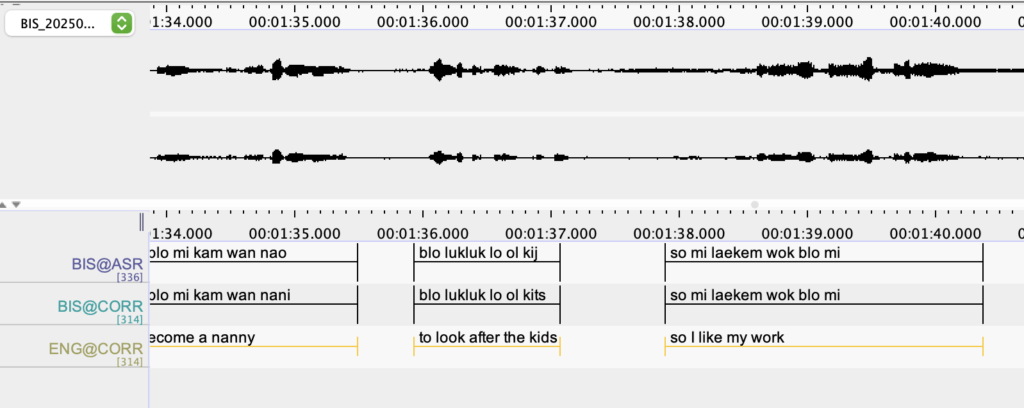

I gave Aso Mahmudi, a PhD student in Computer Science at the University of Melbourne 38 hours of transcribed audio and he has built an ASR system that has segmented and transcribed 22 hours of previously untranscribed audio. This is an amazing result and the quality of the transcript is high, but nevertheless requires checking. In the screenshot above of an Elan file you can see the top tier which is the automatic transcription, the second tier is the corrected version, and the third is the automatically generated translation.

Raphaël Merx, another PhD student at Melbourne, used the parallel text of the Bislama transcript and English translation to produce a Bislama translation tool. While based on around 6,500 sentences, and in a particular domain (disaster recovery), it is nevertheless a very good service. Given that the government of Vanuatu has a constitutional duty to translate all legislation and government paperwork into French, English, and Bislama, a tool like this could save them considerable time. I have shown it to the Vanuatu Language Services Department who are supporting an application to DFAT to develop this system.

A separate project run by Dr Ting Dang at Melbourne, has a Masters student (Jiasheng Xu) working with my transcripts of Nafsan (central Vanuatu) to create a model for transcription of untranscribed recordings. The plan here is to then move the same model to the neighbouring languages of Lelepa and Ngunese, and then to work on a model that can work for the many recordings in the PARADISEC collection from similar languages that have virtually no metadata.

For all of this work, the quality of the audio is obviously a major factor in its usefulness for transcription. Field recordings made in the past are of variable quality, and that is reflected in the accuracy of the transcription.

This week, Raphaël Merx has put the corrected transcript in Bislama through the translator and we now have a transcribed, corrected, and translated recording (as you can see in the screenshot above). Furthermore, the ASR process takes an audio file as input and creates an Elan file, and the translation tool takes the Elan file and returns an Elan file as output, making it very user friendly for the ordinary working linguist!

Added November 7th: Raphaël Merx has now put the Elan tier translation tool online (https://elan-trans-api.rapha.dev/). You drop your .eaf file onto it, specify which tier to translate and the name of the new tier it will create, select which language to translate from/into, and wait for it to process the file. Then download the translated .eaf file.

Thanks to Kirsty Gillespie, Lila San-Roque, Sam Passmore, and Mae Carroll for their work on the Pacific Creoles project. The recording shown in the image above was made by Kirsty Gillespie. Work in Vanuatu was led by Robert Early and Ricky Taleo.

The ethical aspects of this research have been approved by the ANU Human Research Ethics Committee (Protocol number: 2022/346).

Follow

Follow