Susan Butler (Macquarie Dictionary) and Bruce Moore (former director of the Australian National Dictionary Centre) would both like to know if there is any update on the origin of the word ‘brumby’. The Australian National Dictionary (1988)—which lists the variants ‘brombie’, ‘brumbie’ and ‘brummy’—records the earliest citation as 1880, marking the origin of the term as ‘unknown’. The entry for ‘brumby’ in Australian Aboriginal Words in English (1990) notes that the etymology is ‘obscure’ and suggests a possible indigenous source in southern Queensland or northern New South Wales. Here too is found the popular story that “the name came from that of a Lieutenant Brumby, who let some horses run wild, but this has not been confirmed” (p. 58). The source of the story is traced to E. E. Morris’ Austral English (1898, p. 58):

Brumby, Broombie (spelling various), n. a wild horse. The origin of this word is very doubtful. Some claim for it an aboriginal, and some an English source. In its present shape it figures in one aboriginal vocabulary, given in Curr’s ‘Australian Race’ (1887), vol. iii. p. 259. At p. 284, booramby is given as meaning “wild” on the river Warrego in Queensland. The use of the word seems to have spread from the Warrego and the Balowne about 1864. Before that date, and in other parts of the bush ere the word came to them, wild horses were called clear-skins or scrubbers, whilst Yarraman (q.v.) is the aboriginal word for a quiet or broken horse. A different origin was, however, given by an old resident of New South Wales, to a lady of the name of Brumby, viz. “that in the early days of that colony, a Lieutenant Brumby, who was on the staff of one of the Governors, imported some very good horses, and that some of their descendants being allowed to run wild became the ancestors of the wild horses of new South Wales and Queensland.” Confirmation of this story is to be desired.

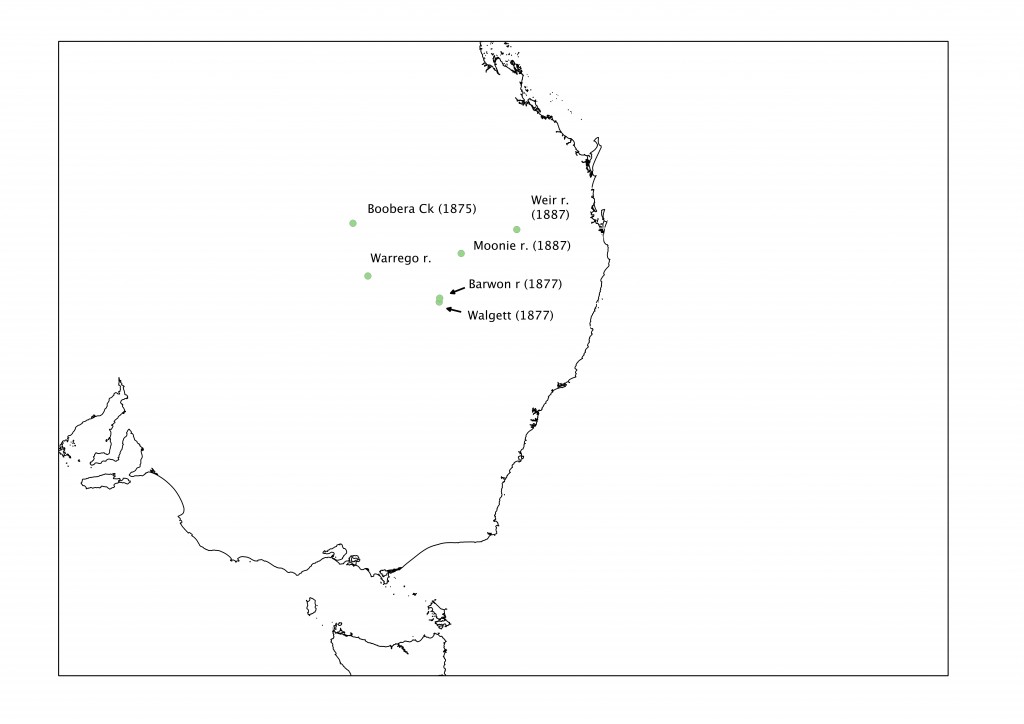

More than a century later, confirmation of this story is still to be desired. As it happens, Morris was mistaken in directly associating ‘brumby’ with the Warrego River. In Curr’s Australian Race, the word is found in a vocabulary collected by a Mr James O’Byrne on the Weir and Moonie rivers further to the northeast. (A separate vocabulary was indeed elicited by Joseph Hollingsworth on “the Warrego and Paroo Rivers” that includes booramby for ‘wild’). His surmise that the word “spread from the Warrego and the Balowne about 1864” is not supported with textual evidence.

Nonetheless Bruce Moore recounts — in What’s their story? A history of Australian words (2011) — that Morris went to some lengths to discover the etymology of ‘brumby’, even speculating that it may have been derived from the place name Brombee where a certain Mr Cox was once renowned as a breeder of sheep, cattle and horses. The whereabouts of Brombee was unknown to him at the time. After having made a public appeal for information in the pages of the Sydney Morning Herald in 1896, he received this intriguing response:

Sir – Referring to the Melbourne inquiry and Mr G. R. Maclean’s reply, the following might assist a little. Amongst the blacks on the Lower Balonne, Nebina, Warrego and Bulloo rivers the word used for horses is “baroombie” the “a” being cut so short that the word sounds as “broombie”, and as far as my experience goes refers more to unbroken horses in distinction to quiet or broken ones (“yarraman”).

In summary, Morris now had reason to back three separate theories on the origin of ‘brumby’: that it was from an indigenous Australian language, that it was derived from the name of a certain ‘Lieutenant Brumby’, that it came from the name of a place. We don’t know whether Morris ever came to a final opinion on the matter. He was to die six years later in 1902.

Thanks to Trove a couple of attestations of ‘brumby’ have surfaced that antedate 1880. The earliest is a short satirical piece in The Queenslander from the pseudonymous ‘A Nervous Cure’, reporting from Boobera on 26 February, 1875 (the text itself was published on 20 March, 1875):

“Ahem! Sir! Pardon me ! Have you ever shot a brumbie?” The question was civil; the answer hot. “What the (warm place) do you call a ‘brumbie’ ?” This, of course, was only answering my question by asking another, and in tones intended to be fiercesome, too; but I told him that a “brumbie” merely meant a wild horse, and mildly suggested that his extraordinary talents as a marksman—as told by himself—could not be put to better account during his brief sojourn in the outlandish country around him—outlandish to him as the Nevada Sierras of which he had spoken.

Another article—”‘Brumbie’ shooting“—published in November of the same year, described the difficulties involved in culling the wild horses. Although the article appeared in the Rockhampton Bulletin there were no direct suggestions that the brumby shooting was taking place in the vicinity of that town. Like ‘A Nervous Cure’ before him, the author did not assume that his readers would be familiar with ‘brumby’, retaining it in quotations marks with a lengthy description of its meaning.

The next instance of ‘brumby’ turns up in a brief report from Walgett in NSW that appeared on 8 September 1877 in Australian Town and Country Journal, and following this it is found in a short article from The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser published on 27 September in the same year. Significantly, this latter article did not define the word ‘brumby’ for the reader. Perhaps by this time the word was well understood in the region.

On Sunday evening there was a great deal of excitement about the Barwon to think that the day had come when the brumbies were to be yarded, and die by the sword, at Caidmurry.

Addressing the hypothesis that the word is of Aboriginal origin, as first proposed by Morris based on Curr, these early citations can be mapped against the approximate regions to which they refer — wherever this information is unambiguous — and correlated with the traditional languages of those areas. The map below plots Boobera Creek (1875), Walgett (1877), Caidmurry run, on the Barwon River (1877) as well as the Weir and Moonie rivers where James O’Byrne contributed brumbi (‘wild horse) and brumbinurr (‘wild horses) to Curr’s 1887 compendium.

Taking a look at Claire Bowern’s coordinates for language areas, the nearest traditional languages to these locations are (very roughly):

Boobera — Badjiri, Margan, Gunya, Gunggari

Walgett — Yuwaalaraay, Wangaaybuwan, Gamilaraay

Barwon River — Yuwaalaraay

Warrego River — Kun/Kurnu, Barundji

None of the vocabularies for these languages have turned up any likely suspects, at least for the data that is immediately available to me. John Giacon and Gavan Breen (p.c.) pointed out that no such –nur suffix exists in Yuwaalaraay or Gamilaraay, as shown in the putative plural marker in Curr (see image above). But if ‘brumby’ has an Aboriginal origin, it is not simply a matter of checking word lists for promising phonological correspondences. After all, horses are clearly an introduced species, meaning that native words for designating ‘horse’ are likely to be either borrowed from English or innovated from within an indigenous language in the early contact period. Likewise, the ‘wild’/’tame’ binary is a distinction that has far more relevance to pastoral economies than it does to hunter-gatherer systems, although certainly many indigenous lexicons distinguish wild from domesticated dogs. It is conceivable that a word resembling ‘brumby’ was available with a different meaning in a local language and this was later transferred, via metaphorical extension, to wild horses. Nothing obvious turns up in southeast vocabularies although interestingly James Günther’s wordlist of Wiradjuri includes burram-bin for ‘white man’ – another introduced species. An aimless conjecture: in the early contact period Aboriginal people would have first encountered wild horses and/or white men on horseback before they encountered white men on foot. This would account for a transfer from ‘white man’ to ‘horse’ when the distinction between the two became meaningful.

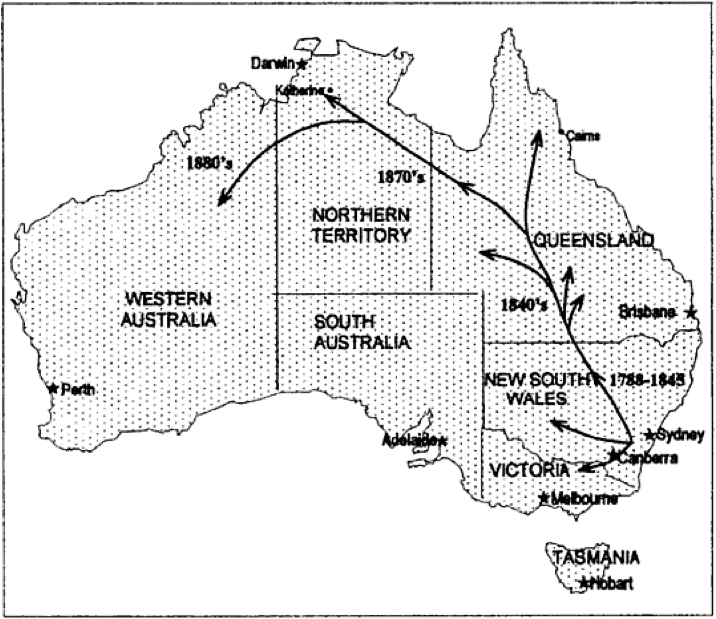

Cultural loans like ‘horse’, of which the generic southeastern term was yarraman, have a tendency to spread quickly amongst language groups as the animal or product is circulated or sighted (and for yarraman and nantu see Michael Walsh.1992. A nagging problem in Australian lexical history. In Dutton, Tom, Malcolm Ross, and Darrell Tryon, eds. 1992. The language game: papers in memory of Donald C Laycock. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics). Indeed, the locations plotted in the map above are right in the path of early pastoral expansion into Queensland, an industry that was incidentally a major vector of NSW pidgin.

Combined, these circumstances make it very difficult to investigate the indigenous hypothesis. By the time O’Byrne and Curr recorded brumbi and brumbinur in 1887 (p258), the word ‘brumby’ had already been in circulation in Australian English for at least 12 years and perhaps longer, since the readers of The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser required no explanatory gloss in 1877. It is thus easy to imagine that brumbi was simply borrowed into a NSW or Queensland language by Aboriginal stockmen from the local variety of English used by white pastoralists. In any case, there is presently not enough evidence available to support or disprove an indigenous origin. Morris’s conjecture that ‘brumby’ came from the place name ‘Brombee’ where a Mr Cox raised fine cattle and horses is worth reviewing briefly. As far as I can tell from a ramble through Trove, James Dalyrmple Cox managed Brombee run in the 1870s which fits with the general time period. Brombee run was near Mudgee northwest of Sydney and even though ‘brumby’ does not appear in print sources for that part of Australia until later, the run would have been on the stock route linking to Walgett, the Barwon, Warrego and Moonie rivers, and Boobera Creek.

Still, all this is as speculative as the supposed ‘Lieutenant Brumby’ whose horses were purported to have run wild. If anyone has any insights on this matter, please let us know!

(Piers would like to thank John Giacon, Gavan Breen, Bruce Moore, Sue Butler and David Nash for their comments and input)

[Update (12/4/2013): In Diana Eades’ The Dharawal and Dhurga languages of the New South Wales South Coast (1976), the word brʌmbi ‘wild horse’ is listed in a table of ‘slang’ words. In Eades’ recollection this word was provided by a ‘rememberer’ of Dhurga who identified it as part of the ‘lingo’. To my mind her account aligns with the 1870s reports where it is described as a term used by Aboriginal people before it entered the settler vocabulary. This strengthens my feeling that in the 1870s, brumby had recently entered NSW pidgin (used by both Aboriginal people and settlers) and the emergent Aboriginal English, and from there it quickly entered Australian English. Supposing NSW pidgin/Aboriginal English is the most proximal source of the term in AusE, then the ultimate lexifier could be any number of lects within and beyond Australia, including, of course, English. Thus, the next place to look would be in contact lexicons, bearing in mind the phonotactics of local languages, as per”baroombie” in the quotation earlier].

[Update (25/7/2013): Samuel Furphy, author of Edward M. Curr and the Tide of History, has informed me that Curr published a book about horse breeding in 1863. You can view it here. Curr discusses wild horses from pages 183-194 and never uses any variant of the ‘brumby’. It could be that ‘brumby’ wasn’t in circulation in 1863, or that he was consciously avoiding it in order to accommodate a wider non-Australian audience.]

Follow

Follow

Here at Endangered Languages and Cultures, we fully welcome your opinion, questions and comments on any post, and all posts will have an active comments form. However if you have never commented before, your comment may take some time before it is approved. Subsequent comments from you should appear immediately.

We will not edit any comments unless asked to, or unless there have been html coding errors, broken links, or formatting errors. We still reserve the right to censor any comment that the administrators deem to be unnecessarily derogatory or offensive, libellous or unhelpful, and we have an active spam filter that may reject your comment if it contains too many links or otherwise fits the description of spam. If this happens erroneously, email the author of the post and let them know. And note that given the huge amount of spam that all WordPress blogs receive on a daily basis (hundreds) it is not possible to sift through them all and find the ham.

In addition to the above, we ask that you please observe the Gricean maxims:*Be relevant: That is, stay reasonably on topic.

*Be truthful: This goes without saying; don’t give us any nonsense.

*Be concise: Say as much as you need to without being unnecessarily long-winded.

*Be perspicuous: This last one needs no explanation.

We permit comments and trackbacks on our articles. Anyone may comment. Comments are subject to moderation, filtering, spell checking, editing, and removal without cause or justification.

All comments are reviewed by comment spamming software and by the site administrators and may be removed without cause at any time. All information provided is volunteered by you. Any website address provided in the URL will be linked to from your name, if you wish to include such information. We do not collect and save information provided when commenting such as email address and will not use this information except where indicated. This site and its representatives will not be held responsible for errors in any comment submissions.

Again, we repeat: We reserve all rights of refusal and deletion of any and all comments and trackbacks.